Troutnut is a project started in 2003 by salmon ecologist and die-hard fly angler Jason “Troutnut” Neuswanger to help anglers and fly-tyers embrace the entomological side of the sport. If you have not visited the Troutnut site before, I highly recommend you check it out as it’s a great resource for anglers. After some recent upgrades to the Troutnut website, I was interested to hear some of Jason’s insights on his work, projects, and adventures. I am happy to introduce Jason to the Blogflyfish readers.

Jamie: What was the impetus for starting the Troutnut website?

Jason: Back in 2003 when I was first getting into fly fishing, entomology, and fly tying, I wanted close-up pictures of my local hatches from multiple view angles, especially the side the fish sees, which is often a bottom (ventral) view. But the pictures in most of the angler-entomology books I had were just small side-view shots (or top view, for nymphs), because nobody could afford the ink to fill a book about mayflies with large, detailed pictures of every species from multiple angles. At the same time, digital cameras were just becoming popular, which made it cheaper to photograph uncooperative insects (rejecting most pictures and saving the few that come out alright) than it was in the film days. So I got a digital camera and started taking the pictures I wanted to use as fly tying models. I shared some of them on forums and got a very positive response. I had been doing some web programming as a hobby and student job since the early days of the internet, so it made sense to put the pictures on a website when I realized there was an audience.

Jamie: When you first started Troutnut, did you ever envision it growing for more than 20 years to be such a resource?

Jason: Not right away. But once it started to take off, my ideas for the site quickly outpaced my ability to implement them. I had the opportunity to spend a full year working on it between college and graduate school, but I have only now at the start of 2025 fully caught up to where I had hoped the site would be by mid-2007, especially as a resource for insect identification.

Jamie: Can you talk about how your professional life and scientific knowledge overlap with your personal pursuits with a fly rod? I am certain your knowledge aids in your fly fishing success, but I am curious how you feel it relates to your enjoyment of the sport?

Jason: There’s a lot of overlap, but not quite what you might expect. I’m still a very amateur entomologist. I describe myself as a salmonid behavioral and population ecologist, meaning I study trout and salmon both on the level of individual interactions with each other and the environment, and on the level of whole-population numbers and the processes that affect them over decades. Of course these levels connect to each other, because a population is made up of individuals, and I’ve worked on understanding those connections too. Does something you see happening to individual fish really make a difference in the population? And when we see a trend in the population, how do we trace it back to what’s actually happening to real individual fish?

My day job since 2022 focuses more on the population side, but my dissertation and postdoctoral research were heavy on behavioral work, especially the study of drift feeding behavior. “Drift feeding” is the technical term for how most of the trout we pursue are feeding: holding a steady position facing into the current and intercepting passing items of food. Because it’s repetitive, it’s amenable to mathematical modeling and understanding, as compared to more chaotic feeding behaviors like chasing minnows around. We can sample the insects drifting in the river, along with some physical variables like temperature and water velocity, and then predict how much energy a feeding fish can gain. That tells us about habitat quality and how it changes with flow, and it can allow us to predict growth under various real and hypothetical circumstances too.

I justify this work to scientific audiences with the fact that feeding is critical link between the environment and the growth and survival of fish, but fly fishing drives my interest in it too. My first scientific publication was about the fact that small drift-feeding fish (juvenile Chinook salmon) spend almost all of their feeding effort pursuing and rejecting little pieces of inedible debris (pieces of leaves, algae, etc.) rather than prey. In later work, I found that this holds true in many species, and for larger fish, although the proportion of time spent on debris decreases because there isn’t as quite much debris of the same size as larger prey. Nevertheless, there is so much debris (even in very clean water) that a typical trout spends its day looking at thousands of drifting items and making the “food or not food” decision for every single one.

Like humans and other animals, a trout’s capacity for “visual attention” is limited: they can only examine so many drifting items per second. If there’s too much to look at, they have to focus their attention. When there’s more debris in the water or it’s flowing faster (more items per second), they focus in a narrower window of space, so you have to either put your fly closer to their nose or make it more conspicuous. And when a particular food source is abundant enough to satisfy the fish, they can focus on that type of prey, turning the complex “food or not food” decision into the simpler “size 12 Hendrickson dun or not” decision. This search image probably makes them better at spotting that type of prey quickly, and it reduces the energy they otherwise waste chasing and inspecting debris. This is how I scientifically view the behavior anglers call “selectivity,” the thing that makes hatch-matching so interesting and effective at times. I have a website for some of my research (especially before my current job) at https://www.jasonneuswanger.com.

Working on these subjects professionally doesn’t dull my interest in fly fishing at all!

Jamie: What is the prettiest small fish you have ever caught on a fly?

Jamie: What is the prettiest small fish you have ever caught on a fly?

Jason: Wild golden trout in their native range. I wrote a detailed trip report complete with photos.

Jamie: The Troutnut photos are amazing and I have found them to be one of the best resources on the web for helpful pictures of aquatic insects. I appreciate the very useful hat-tip to anglers with the handy hook size chart often in the background! Your pictures of the adult caddis fly Hydatophylax argus (Great stencil-wing sedge) are stunning. Can you share a few more of your favorite insect photos?

Jason: That Hydatophylax is one of my favorites, too. The 2025 update to the Troutnut website includes a photo collection that just highlights my favorite insect photos separately from the main library of species descriptions.

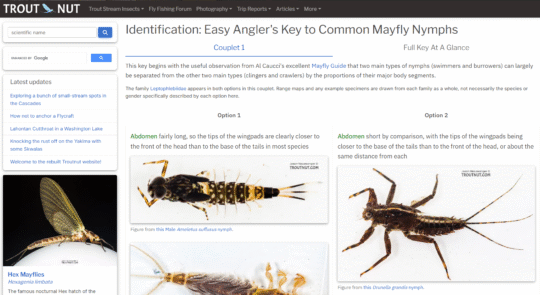

Jamie: Taxonomic keys for aquatic insects are varied, often confusing, and littered with unique verbiage. When I was ID’ing insects, I had to make my own keys that combined and translated information from many sources for my own area. What was your approach to developing the new keys recently added to Troutnut.com?

Jason: I thought keys were a good extension of the initial idea that started Troutnut, trying to take full advantage of the opportunities of a digital medium to create something much more useful than what was possible on paper. Most taxonomic keys are still in books, and even the online versions mostly follow the familiar format you’ll find in books. These existing keys represent an incredible and ongoing accomplishment by the taxonomists who assemble them, and I’ve contributed almost nothing myself to the scientific substance of telling one bug apart from another. But I’ve used keys enough to grow frustrated with the many tedious little steps that were always necessary evils when using paper keys, like having to flip around between pages to find illustrations, and having to search back through a wall of text when backtracking from a dead end. They’re minor things, but they add up fast, to the point that it’s easy to spend most of your insect identification time doing steps that shouldn’t really be necessary.

The keys now on Troutnut eliminate most of that busywork and streamline the process of identifying insects, so most of the time is spent actually looking at and learning about them. That’s still time-consuming, but it’s all the fun part if you’re into that kind of thing. And I would encourage people to give it a try with a small dissecting microscope or whatever other tools they have at their disposal. Identifying your local hatches with more taxonomic detail will only occasionally help you catch more fish, but it becomes satisfying in its own right, in a similar way to birding. If you see an unusual bird on the river, and you recognize it and understand that it just flew two thousand miles from the Arctic tundra to get to you, that makes your day on the water more interesting. Knowing your aquatic insects can enrich your days on the water in the same way, because you can have fun spotting something rare, or a species with an interesting behavioral story.

Jamie: With your effort to update and refresh the website, what are you most excited about?

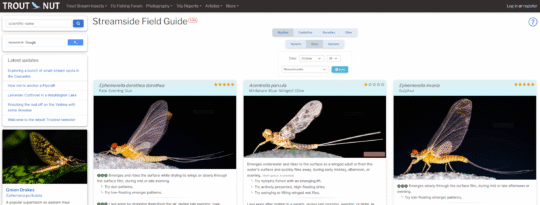

Jason: My favorite new feature is the streamside field guide. Those of us without microscopes for eyes don’t have the time or ability to look at the true identifying characteristics of most insects (tiny mouth parts, hairs, etc.) on the water, so we have to rely on the general look of the bugs at a glance, however imperfect that is. Written field guides get you part of the way there, but most of us don’t carry those in a vest. Also, written guides only have enough paper and ink to cover the most common species, and in my experience (maybe partly due to fishing the West for so much of my life) most of the hatches I see aren’t the big-name ones that appear in books. The stream side field guide on Troutnut gives you all the common species and the obscure ones, matched to your location anywhere in North America. It includes the most relevant bare-bones information to hatch-matching, such as whether a species emerges on the surface or by crawling out on the rocks. There’s limited information available anywhere about many species, so the guide often borrows from related species, but it tells you when it’s doing that.

Learn more about Troutnut.com or support the project for an enhanced experience.

All photos copyrighted and courtesy of Jason Neuswanger of Troutnut.

Discover more from BlogFlyFish.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.